To improve in the future, the Nets will have to learn from the mistakes of the past. In this weekly series, Nets are Scorching writers Justin DeFeo and Devin Kharpertian take a look at how the Nets performed in different sets on both sides of the ball during the 2010-11 season.

Frankly, the Nets were terrible defending the pick-and-roll. New Jersey ranked 21st in the NBA at defending the roll man, and 27th at defending the ballhandler. Surprise! I put the end of the story first. If you’re not interested in all that analysis-y mumbo jumbo, you can move on to the next article.

If not, keep reading.

What Needs Improvement

1) Communication. Communication is so key when trying to defend the pick & roll, since defending the play inherently relies on two defenders communicating with each other, and then the remainder of the squad being able to adjust to their decisions. However, the Nets (especially their backups) just showed a complete lack of communication on a number of pick & rolls.

In the play above, Alexis Ajinca (guarded by Brandan Wright) sets a screen on the left wing for Jerryd Bayless (guarded by Vujacic). Wright calls to Vujacic to tell him he’s rotated over, but Vujacic doesn’t hear him or doesn’t listen to him. Wright, dumbfounded, yells at him to stay over on Ajinca, but by this point Ajinca already has the ball and is spotting up for a wide-open three. Even though Ajinca misses the shot, the defensive lapse is evident; Wright even raises his hands in confusion and disgust as Vujacic runs into him.

That’s not to say that it’s more Vujacic’s fault or Wright’s. Perhaps since Vujacic was able to get around the screen so quickly, Wright should have known to react by staying with Ajinca. That confusion is exactly the problem. The communication doesn’t exist.

The problems with communication also hurt the Nets when they attempt to guard the ballhandler:

On this play, Landry Fields receives a cross-court pass from Carmelo Anthony. Fields immediately receives a pick from Jared Jeffries, and his defender (Stephen Graham) automatically trails Jeffries. The problem here, though, is that Brook Lopez does the exact same thing: he steps back in order to cut off Jeffries’ path to the basket. Neither one says anything, and by the time Lopez realizes it, it’s too late: Fields has a wide open jumper.

2) Awareness. Communication and awareness go hand in hand; without communicating with your teammates on defense, you won’t be able to fully understand your surroundings. That’s why teams like Boston or Miami have such well-run defenses; not only are they athletically gifted, but they’re constantly in the middle of a running dialogue. That conversation leads to an innate, instinctual ability to defend against standard offensive sets.

The Nets this year did not have such a dialogue, and as a result, often lost their defensive assignments. On these two plays below, it showed:

On this first play, Rajon Rondo and Glen Davis execute a pretty standard pick-and-pop on the right wing, with Davis extending out to about 18 feet. However, Rondo’s man (Anthony Morrow) completely disregards Davis, as do the rest of the Nets. Take a look at the heads of every Nets player during the freeze frame: with the exception of Travis Outlaw (who’s too far away) and Deron Williams (who can’t leave Pierce), no one is bothering to even consider Glen Davis’s existence. Morrow even has his back to him.

This second play is nearly identical. Replace “right wing” with “left wing,” Anthony Morrow and Brook Lopez with Jordan Farmar and Kris Humphries, and you’ve got the same situation: poor trap in the corner, nobody watching the pop, and the Celtics get a wide-open jumper. Even the freeze frame shows the lack of interest. This was an issue with the Nets throughout the season, and for whatever reason they could not consistently adjust.

These are the types of plays that get under my skin. Not the emphatic jams – those are going to happen. But the small mental mistakes can swing the momentum in every single game, because they come up almost every single play.

3) Quickness from the bigs. This was perhaps the Nets’ biggest problem defending the pick and roll. Often, the Nets bigs were simply not quick enough to rotate to guards, or were simply outrun by an athletic big. They just don’t have any great athletes with the requisite foot speed to stay in front of guys who rely on their agility. While the blame was on everyone, it was on no one more than Brook Lopez.

That said, I don’t just mean physical, lateral quickness. I also mean mental quickness; the ability to adjust on the fly to the offensive set presented. This example from a Nets-Clippers game highlights both a failure of athleticism and mental preparation in defending the pick & roll:

Although it’s as much a transition play as it is a pick & roll, what you see here is a double failure by Humphries: first to adjust for Griffin’s athleticism, and second to understand the space on the floor. Humphries sees Griffin about to set the screen and instinctively goes to hedge. This would make sense if there were defenders behind him ready to rotate to a rolling Griffin, or if Griffin was coming up from the block to set the screen (since his momentum would be carrying him away from the basket).

However, Humphries’ decision to hedge the screen leaves the entire left side open, and since Griffin’s momentum is already carrying him towards the basket, he dives right in for the roll and gets the easy finish.

This mental failure doesn’t just happen on dives to the basket by SuperGriff, though:

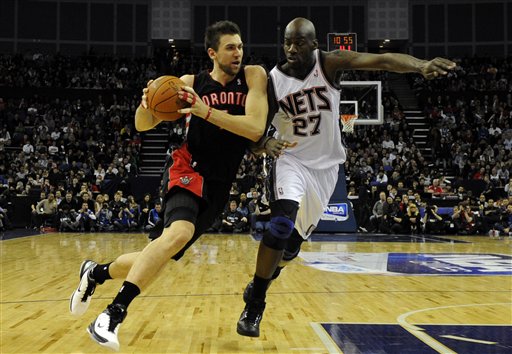

Here, the Raptors run a high screen with Andrea Bargnani and DeMar DeRozan. DeRozan is a slasher without a lot of outside shooting ability, while Bargnani’s a deep threat and a poor screener. Sasha Vujacic quickly dives under the screen and stays with DeRozan, cutting off a potential lane to the basket. However, Humphries doesn’t react quickly enough to that situation, instead opting to stay with DeRozan to further cut off the lane. By the time he realizes his mistake (you can hear him yell “oh!”), Bargnani is wide open at the top of the key and knocks down the easy three.

What They Did Well

1) Having Deron Williams. No, seriously. If the screener in a pick & roll is getting a pass, that usually means he’s getting it in a position to score. At that point, it just becomes a numbers game; you want to minimize the amount of times you allow a roll man to get into the lane or open for a pick-and-pop. Against any team, you’d much rather that the ballhandler be forced to create an offensive opportunity for himself, because a well-played pick & roll defense essentially forces an isolation.

This is another area where having a superstar like Williams becomes key. His combination of size, lateral quickness, and awareness make him a very good defender (when motivated) in pick & roll situations. His eagerness and strength allow him to go over the top of screens more often, leading the attacker into a rotating big. However, his impact will be completely neutralized if the Nets don’t get good rotation defenders around him to close on spot-up shooters and get in that lane when Deron goes over the screen.

– – – – – – – – – –

Looking At The Numbers

- According to Synergy Sports Technology, 20.7% of plays completed by the Nets this year were of the pick & roll variety. Nearly twice as many plays were by the ballhandler than by the screener. That’s not as bad as it could be, but it certainly shows both a failure of Nets guards to find the screener rolling to the basket, as well as a failure of the screener to get a good look.

- The Nets were also average at cutting off the screener themselves. While the Nets defended the pick & roll 15.7% of the time, 4.4% of that was on the roll. While the Nets weren’t great at stopping the screener once he’d gotten there – they were just 21st in the NBA in efficiency – they were able to use the roll man far more often than their counterparts. That’s key.

- By the numbers: In a small sample, Deron Williams was the best Nets defender in ballhandler pick and roll sets, allowing just 39 points on 53 possessions. The worst? None other than Stephen Graham, who saw the same number of possessions, yet allowed 54 points – 15 more.