Dear Jason Collins:

Let me preface this by saying you have no obligation to listen to me. We both know that. I am a lowly editor of a local sports site that happens to cover the team that helped you make history a few months ago. You are a professional athlete, a sports icon, and perhaps most importantly, an adult with agency. Your pursuits are your decision.

You’ve taken time this summer to roam the speaking circuit, using your voice at the Inforum Convention, holding a public forum with out ESPN editor Kevin Arnovitz, and attending various other events around the country, after becoming the first openly gay male athlete in one of the four major professional US sports.

It also appears that, at 35 years old, you’re legitimately torn about whether you’d like to keep playing next year, waiting until the end of the summer before you decide on your next step.

So with that in mind, know that I mean this from the bottom of my heart, from the same place that wants the world to be a better, more inclusive place for all.

Please never play in the NBA again.

I know media members and professional athletes that privately cheered for you every time you took the floor this past year. I was one of them. They (we) recognized that your mere presence on the court post-coming out signified a major step in the progression of history, both immediately and retroactively dismissing the idea that a gay athlete could not peacefully exist in a professional locker room.

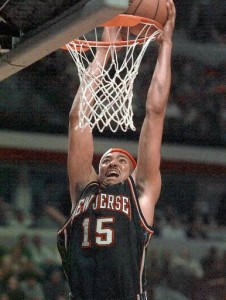

Long before most people knew your name, you were, weirdly, an inspiration to me: an awkward teenager with bad teeth and little control over an oversized body. I played low-level basketball from 2003 to 2006, in my brief public high school career in northern New Jersey, right around the time you were paid to give six fouls per game against the world’s best post players.

In your prime, you were the original no-stats All-Star, before Daryl Morey and Shane Battier made it basketball nerd chic. Year after year, you ranked among the league’s best in on-court/off-court impact despite your complete lack of box score statistics.

I was told to play like you, or I wouldn’t play at all. My teammates called me Nenad because I’m from Eastern European descent and could hit the occasional 15-foot jump shot, but I played your role way more than his: I stayed in the middle of the floor with my hands up, I bumped cutters, bodied larger, more agile big men out of post position from the legs up, and yelled a lot on defense, even if it was just to yell. Someone’s got to do the grunt work, and you were the Michael Jordan of grunts. My coach might as well have given me a Jason Collins basketball card when we talked about what he wanted me to do. I didn’t want to be like Jason Collins. Nobody wanted to be like Jason Collins. I just did it to fit in.

The only time you led the NBA in anything was personal fouls (322) in 2004-2005. Like you, I fouled. Oh man, I fouled. I fouled so much I got into fights with opponents on a regular basis. My motto was “I’ve got five fouls, I might as well use them.” In one game, the referees lost count of how many times I’d hacked an opposing big man, and eventually told me to just get the hell off the court. My unofficial foul count was nine. You would’ve been proud.

Those days are long gone for me, and the same’s true of you. Your on-court rating this past season was the worst in your career, only better than Marquis Teague among Nets that finished the season in Brooklyn. The team performed 12.2 points per 100 possessions better with you on the bench. Small sample size? Sure. But you’re also 35 years old hanging onto ten-day contracts. There’s a reason it was a small sample size in the first place.

But this time around, your impact had nothing to do with your on-court impact. In perfectly Jason Collins fashion, you turned from the no-stats on-court All-Star into the the no-stats off-court All-Star.

They’re at the GLSEN Conference and in pride parades and Division I colleges like your alma mater Stanford. They’re with families that aren’t sure how to deal with knowledge they’ve never had to process. It’s safe spaces where people need to hear that it’s okay, it’s okay if their teammates or opponents are different, or their coaches, or their friends, or themselves. It’s a safe space only you can cultivate, because you’ve been there in a way that few could understand and experience. You can relate because you’ve walked the path they want to walk, not just in professional sports, but in becoming an adult comfortable in his or her own skin.

I had to miss one practice in my sophomore year because of a sinus infection. After a crude game of telephone, it got back to my coach as an anus infection. That led to, well, you probably get what. I was uncomfortable. It’s weird being forced to explain you aren’t gay when you’re 15. But I played along, because I didn’t have the voice or strength to explain why. Maybe you do.

With 13 NBA seasons under your belt, you’ve had a longer career than 95 percent of the nearly 4,000 players in league history. You’ve made nearly $35 million in NBA salary since your rookie season, when some late first-round picks don’t even get a second contract. You’ve been a consummate NBA professional for 13 years. On the court, you have nothing left to prove. Off the court, you have a world of difference to make.

This is just one man’s suggestion. You’ve carved out an impressive life for yourself. Me, I have no idea what I’m doing. Maybe you want to still play, and that’s fine. Maybe you want to do absolutely nothing, and that’s fine too. But you’re also unique: an NBA player, one of the best at his profession in the world, who’s better suited for his next job than his last one.

Sincerely,

Devin Kharpertian

The Brooklyn Game

devin@thebrooklyngame.com