A couple minutes into Jason Collins’ first appearance for the Nets on Sunday, my wife said what has become a common chorus, “Why is this such a big deal? It shouldn’t be.”

And that’s right. But it is a big deal. A thing can’t happen until it happens. And now, days removed from this game, she’s even more right. Today, the fact that there’s an openly gay man in the NBA isn’t a big deal. But on Sunday night it was. Jason Collins checked into an NBA game and went to work. He made it not a big deal, and that is a big deal. He created one more safe space.

By the end of the fourth, the fact that Jason Collins is gay wasn’t really of any importance. The game ended, Kidd talked to his team, they left the arena, I washed some dishes, and everyone else in the country did whatever they normally do on Sunday nights in America. It was one of the smallest, most fleeting historical moments in this country. It mattered greatly, but only for a few seconds.

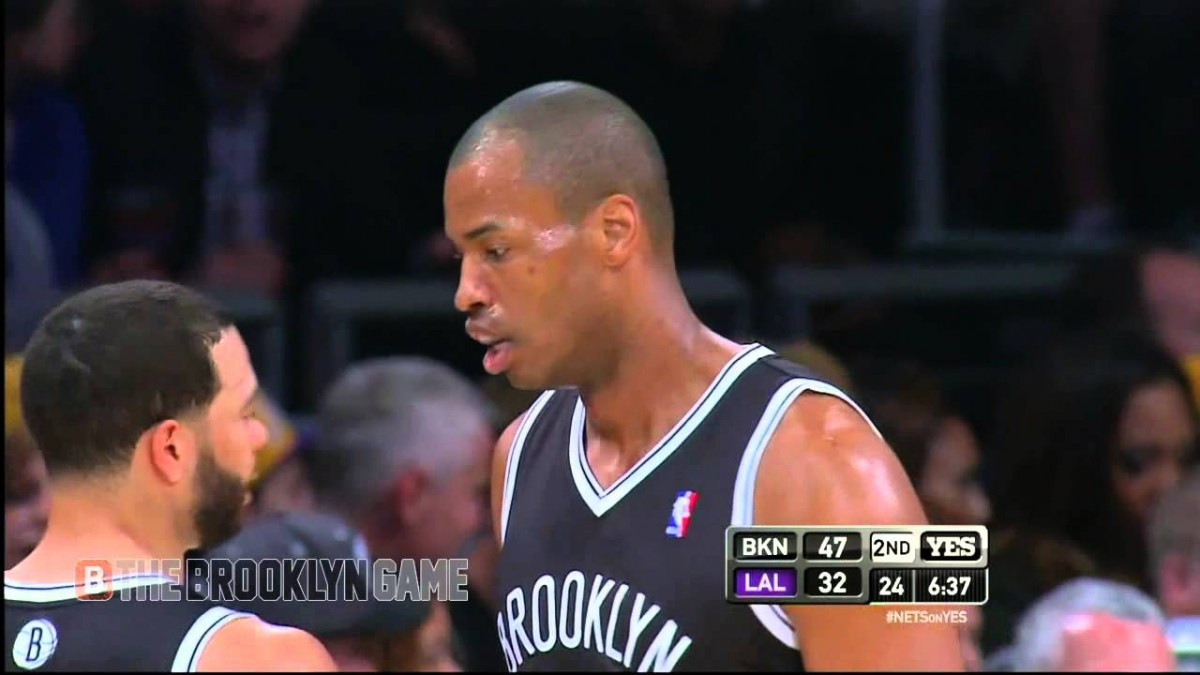

At one point in the game, Collins got knocked down, and Deron Williams, Alan Anderson and Andrei Kirilenko all rushed over to help him up. He’s a big dude, but that’s much more help than he needs to get up off the ground and all three were there to extend a hand fast. The hyper-eagerness was comical, but also pretty adorable, if only because three guys saw an opportunity to help up their brand new teammate, a guy who at that point had been part of their team for around six hours.

The play itself was a rebound attempt by Collins, but the YES replay made sure to show the moment of camaraderie one extra time before letting the live camera linger on Collins for a bit. I know it’s a very small gesture, and OF COURSE the guys on the team are going to help up Jason Collins when he falls down (which is going to happen a lot, considering the dude loves taking charges and is really just kind of uncoordinated for an NBA player), but also, it’s kind of an important moment. Because it’s the first time an openly gay player in the NBA was helped up by his teammates. And now it’s unimportant if it happens again.

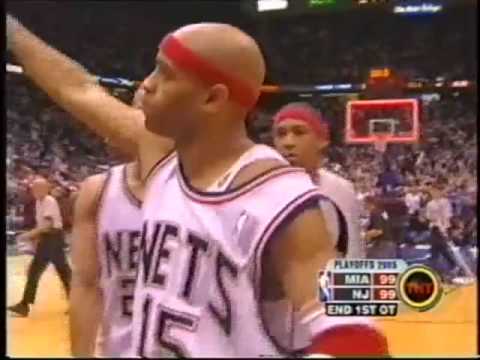

I’ve been talking about Jason Collins with my father for close to 14 years at this point. As two people who invested greatly in the Kidd-led, early-2000s Nets, the two of us have pretty strong opinions on the guy. For most of his career with the Nets, the conversations were basically one of us reciting the prior night’s Collins stat line to the other, incredulously noting the lack of points or rebounds and glut of minutes. If we were watching a game and Collins grabbed five rebounds in the first half, you better believe one of us was going to exclaim in faux-astonishment what a dominant performance he was having.

In those pre-Sebastian Pruiti/NBA Playbook days, we relied on our eyes first (Collins’ stone hands and lack of athleticism stood in stark relief to the streaking Nets of those days), newspaper box scores second, and nothing else third. I wasn’t using our DSL modem for much else besides playing “Counterstrike” back then, but even if I was, I wouldn’t have been able to locate the surplus of savvy basketball writers that exist today, eager to explain Collins’ effectiveness. So all we knew was that Jason Collins didn’t grab enough rebounds for a seven-footer, regularly fumbled Kidd’s passes, fouled at an extraordinarily high rate (he led the league in the 2004-2005 season with 322 personal fouls) and got absolutely torched by Shaq in the 2002 NBA Finals. Simply put, we were not Jason Collins fans.

Cut to Saturday afternoon: I’m eating lunch with my dad at The Fireplace, a legendary north Jersey hamburger shop on Route 17. The Nets come up, as they always do, and (after offering his condolences for the departure of Reggie Evans), we talk about the possibility of the Nets signing Collins. Echoing the general narrative arc of Collins’ post-Nets career, we both agreed that he could be a serviceable third-string center who would talk on defense and be good for six fouls, a few drawn charges and at least one botched pass per game. The versions of us from 10 years ago would be unhappy with our acceptance of Jason Collins the basketball player, but clearly, great progress has occurred in the past decade.

Then on Sunday, the ink dried and Jason Collins pulled off an incredible feat: Inciting historical social advancement while being a hulking, fundamentally sound, deliberately boring basketball player. He checked into the game, the first openly gay man to ever do so in the NBA, and then: He kicked the ball, set a tough pick for Deron, ran around some more, got called for an illegal screen, let a loose ball sneak through his hands…

Point is, he’s still Jason Collins. He came in, broke down an embarrassingly stubborn barrier, and immediately became Jason Collins again.

And that’s why Collins is such an appropriate dude for this: He’s a boring basketball player. His stat line from Sunday was exactly the type that my father and I would have ridiculed during Collins’ first stint as a Net: 0-1 from the field, two rebounds, zero assists, one steal, zero blocks, two turnovers, five fouls, and a +8. The quintessential (i.e. pedestrian, slow, effective) Jason Collins game. He was able to let his play quickly take the air out of a highly charged event that needs to become commonplace in sports (and has long been commonplace in most other American workplaces).

Right before the game, I texted my dad: “Jason Collins!” His response was spot on, perfectly displaying the combination of excitement and banality that this moment has engendered; exciting because it’s truly a watershed moment for American sports, and banal because once Collins played in an NBA game again and made history, the immediate result was still just Jason Collins playing boring basketball for the Nets:

“That’s great. Good move.”