When we discuss tunnel vision in basketball, we generally refer to the idea of a singular player that takes the challenge of deconstructing the opposing defense single-handedly upon himself. Images of Nick Young, Jamal Crawford, Brandon Bass, and other point-focused, ball-domineering players flash across our consciousness. There’s often little more than the ball, the first line of defense, and the basket in their frame of vision.

What we don’t often talk about, and can often be as damaging, is this particular propensity to over-focus while playing on the opposite side of the ball. Not tunnel vision offense, but tunnel vision defense (TVD). As I’ve mentioned before, I like calling it TVD because TVD makes it sound more like a disease, which it is; complete with symptoms (slow rotations, poor communication, staring down the ballhandler or secondary offensive option) and damaging effects (points on points on points).

Currently, the Nets allow their competitors 112.2 points per 100 possessions, the worst in the NBA. They’re almost four points worse than their nearest “competitor” (Sacramento) and ten points below the current league average of 102.4. (It should be noted that the league average is normally higher, but the shortened and rushed season has taken its toll on efficiency.)

TVD is the biggest reason the Nets are scraping the barrel bottom of history. Some examples of its manifestations, in the biggest problem area, after the jump.

Three-point shooting

The Nets’ inability to defend against the three-point shot is approaching historic. Through 11 games, they’ve allowed 46% shooting by opponents from beyond the arc, by far the worst in the NBA. The NBA record for opponent three-point percentage in a season is 41.1%. They’ve given up 92 three-pointers (8.4 per game), the most in the NBA. The NBA record for three-pointers allowed per game is 8.3. They’ve allowed over 60% shooting from 3 three times. No other team this season has allowed 60% from outside more than once.

According to mySynergySports, the Nets have allowed 1.05 points per possession on spot-ups, ranking — you guessed it — last in the NBA. Well over half of those points have come from three-pointers, and opponents are shooting over 43% from outside in those instances.

If the Nets were merely league average at defending the three-pointer, the team’s defensive rating would decline by nearly eight points per 100 possessions, from 112.2 to 104.6. That decline represents about seven points per game, and moves the Nets from 10 points above league average to a little over two.

TVD is the problem. Every player is a culprit.

Throughout the early season, the Nets continually fall victim to unnecessary ballhawking defense, cutting off lanes that don’t need cutting off, pushing irrelevant, unhelpful double-teams, and leaving their assignment purposelessly. Occasionally it manifests as a domino effect; once one man screws up, the unit remainder falls in line trying to rectify said screwup, and the instinctual need to cut off direct lanes leaves indirect ones wide open. With the amount of open looks the Nets have given up in the first 11 games, 46% hardly seems surprising.

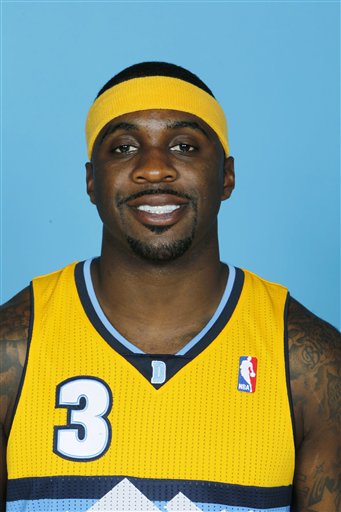

There are many strains of TVD across the NBA landscape. Andray Blatche invents at least two new ones each year. TVD has affected the Nets all season, but you only need to look at the most recent game — the non-blowout-blowout against the Denver Nuggets — to see the many ways TVD can destroy your defense.

The double-team TVD

This play starts with Danilo Gallinari throwing an entry pass in to Nene on the camera-side block. Once Nene has position, Gallinari, guarded by Anthony Morrow, begins cutting to the right side. Morrow appears to trail him, when suddenly…

“Wait! I’ve got a better place to take my defensive talents!”

Morrow begins his inexplicable eagle-swoop on Nene, completely abandoning any notion of guarding Danilo Gallinari, a career 37% three-point shooter, leaking out to the perimeter.

Nene, a 7′ center, barely notices the 6’5″ Morrow occupying the less-than-crucial space between Nene and the perimeter, but he does notice that the Rooster is now somehow unguarded and fires a pass to him.

As seen above, Gallinari’s openness forces MarShon Brooks to leave Arron Afflalo, a career 40% three-point shooter, wide open at the top of the key. Morrow, not known for his defensive intensity or fleetness, doesn’t recover in time to contest the shot.

Here is the play in real-time:

It’s tunnel vision defense like this that force analysts to bestow the marker of “worst perimeter defender in the NBA” on Anthony Morrow. Morrow starts off by needlessly abandoning a phenomenal perimeter player on the perimeter, choosing instead to involve himself immediately with the ballhandler — a player bigger and stronger than him. After his double-team fails, he then floats to the top of the key to guard air on the skip pass, before trotting his way out to barely contest Arron Afflalo’s three-pointer. Without the original TVD forcing Morrow to beeline for the ball, this breakdown doesn’t occur.

Morrow is hardly the only culprit. In this video below, you’ll see Deron Williams make the identical mistake:

Different guard, same story: D-Will scurries to defend ballhandler Nene in a double-team, Nene kicks out to the open man, who then swings the ball to the next open man (Gallinari in this case), who buries the three-pointer.

What Morrow and Williams are hoping to accomplish by flashing a double-team on Nene — a center known for his immense strength, intelligent offensive game, and unselfishness — is beyond my comprehension. I can’t imagine it’s part of the game plan, but if it is, well, it’s a horrible game plan.

The over-help TVD

This one is less egregious than the double-team, but just as harmful; it occurs when a defensive player off the ball leaves his perimeter assignment just a bit too much, giving the offense enough time to fire a pass and get a quick, clean look.

An example below:

At the start of this play, Gallinari (arms extended) receives a pass at the high right post, guarded by the ultra-long rookie MarShon Brooks. Extra E (upper left corner), guarding Corey Brewer, sees the matchup and proceeds to get in help position.

Extra E’s in just the right place that he can help cut off Danilo if he gets past MarShon, but close enough to close out in case there’s a pass to the corner.

Wait… Shawne, no need to inch down. You were fine before. He hasn’t moved towards the basket, or even taken a dribble yet. No need to sag that far off.

Wait — no — Shawne — where are you — why are you — now Gallinari sees you down low, which means he knows that —

That’s all the space Brewer needs to hit the shot:

The swarm TVD

This is the deadliest form of TVD of all. A complete breakdown in communication results in at least three players diving towards either the ball or the basket, leaving multiple options open in multiple spaces.

In this instance, swarm TVD came with the Nets down 15 in the 3rd, with Deron Williams embarrassed on the bench. The Nets decide to throw a zone at the Nuggets, even though a zone isn’t exactly the defense you want against a team killing you with open jumpers. To the surprise of no one, the Nuggets break it down in a matter of seconds.

There’s only one screenshot you need to see to understand swarm TVD:

In this one shot, we’ve got:

Gallinari chose to pass to Rudy Fernandez on the right wing for the wide-open three. Here is the play in real-time:

Fixing a problem like TVD is not easy; there are no overnight solutions. The team boasts just two players over 30, and eight 25 or younger (including Brook Lopez); it’ll take some combination of time and transactions to get the defense on the right track. It’s difficult enough to develop defensive skills for the individual, much less revamp the entire team concept. The archaic cliches of defense all apply. Keep your head on a swivel. Anticipate the offense. Start moving when the pass is thrown, not when it gets there. Focus on five, not on one. And so on. The words mean nothing without practice and patience.