By MICHAEL SHAPIRO

When you grow up in the Brooklyn I knew, which was pretty much the worst possible time – just missing the Dodgers and years before it got so cool – your memories of the place are almost always flat, dull and gray.

My Brooklyn, circa 1952 to 1974, (from birth to graduation from Brooklyn College) was a place you were supposed to leave, for college, Staten Island, Nassau County, Jersey or if you were exceedingly lucky and unusually ambitious, “the city.” And yet, years later, there was still a sense that it all could have been so much better. Brooklyn did not have to be the place where there never seemed much of anything to do except to talk about all the good things that waited to be done when you finally bade the place goodbye.

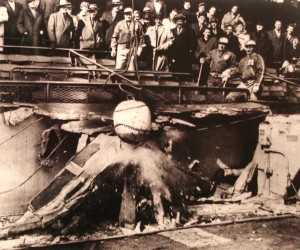

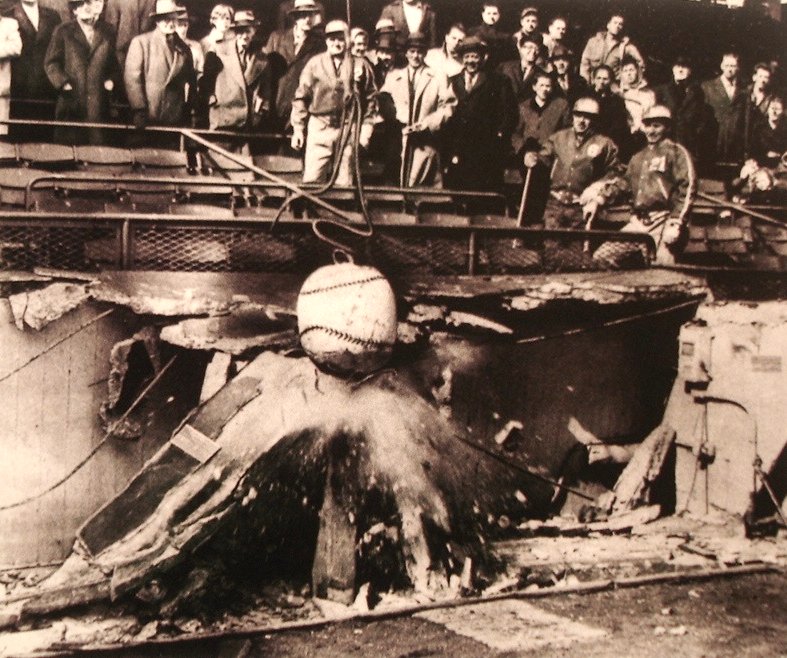

The Dodgers had a lot to do with that, especially if, like me, you’d never been to Ebbets Field and so could only imagine a time when the little ballpark was always crowded and the days always sunny and the Dodgers, the sainted Bums, always beloved. We who arrived too late had no splendid not sure of this word. Splendid? Ironic, but not quite sure….memories of hot dogs turning green as they boiled their way through the second game of an August doubleheader, or the acrid smell from the Ebbets Field bathrooms.

As it happens, some years ago, I set about trying to live those happy years vicariously by doing what writers do and recreating that time through other peoples’ stories. I learned, not surprisingly, the reality was not what we’d come to remember.

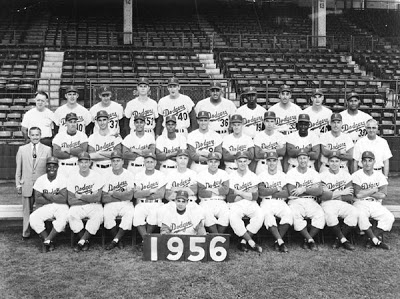

To begin, we have come to assume that the faithful adored always, despite all the many years when the team, the bums, the “daffiness boys” languished in the second division and attendance was limited to those without gainful employment. Actually, their departure was more painful because, while the Dodgers had spent much of their long history being quite bad, from 1946-1956 they were were surely the best team in the National League and the second best in baseball. Yes, they lost to the Yankees four times in the World Series, but they had five trips to the series in ten years. And one, there-is-a-God world championship, in 1955.

Better still, the Dodgers were built around a familiar core – Reese, Robinson, Campanella, Labine, Snider, Erskine, Hodges – most of whom lived not only in Brooklyn, but in one neighborhood, Bay Ridge, where there sons played in the local little league and their wives shopped at Rossi the butcher. The players carpooled to the ballpark. Kids rang their doorbell for autographs.

They were great and they were neighbors.

Truth be told, there was no public rending of garments when the team left, and while there were the occasional rallies, Brooklyn let the Dodgers go, grumpily perhaps, but not barring their way. The Dodgers and the old little park where they played represented the past and in 1957 the past possessed all the allure of moving back in with your parents the day after your wedding. The past, the stoop, an egg cream at Ben Chodesh’s soda fountain, mandatory Sunday dinners at Lundy’s paled in comparison to the good life that beckoned elsewhere.

Who needed life facing out onto the street, with all the noise and gossip and the old ladies who spent their days leaning their elbows on pillows perched on their window ledges, who needed everyone breathing down your neck, and talking in your ear – Frank, watcha doin’ Frankie boy?— when for a modest thousand bucks down you could own a split level in Syosett, where life looked out on what seemed like the endless expanse and welcome stillness of the backyard?

And that sentiment prevailed for a generation and more. In places like Brooklyn, those few people who began filtered in from Manhattan in search of brownstones in neighborhoods like Park Slope (where the locals were embarrassed to confess where they lived; trust me, I heard it) were regarded as pioneers.

In hindsight, though, it is clear that when the Dodgers left, the borough lost not so much its soul as its conversation. For as long as most anyone could remember, the Dodgers had represented the one topic that this big, messy, disparate collection of strangers, friends, familiar faces from the luncheonette, parishes, VFW chapters, ladies auxiliaries, scout troops, reading groups, bowling leagues, and Kiwanis clubs had in common.

Then the team left. And what was there left to talk about that might be of interest to most everyone?

Now, 55 years later, come the Nets. And the Islanders. Who together will play 82 regular season home games at the Barclays’ Center, one more than the Dodgers would have played had they stayed. But will it be as once was? Will Brooklyn take to the new teams as it once embraced its “bums?”

Or is something new about to unfold in a place where, from a big league point of view – sorry Cyclones — time has stood still since 1958?

What we have seen in the last decade or two might be called the Rejection of All Things Robert Moses, and the embrace of the World According to Jane Jacobs, a view of urban life that held that cities were made great not by the width of their highways or height of their buildings, but by the pulse of life on their streets, where the conversation happened. The Brooklyn Nets arrival signals the flourishing of the New City as much as the departure of the Dodgers signaled the death of the old city.

In the sporting context this profound change in taste was made apparent in 1992 when Camden Yards opened in Baltimore. Suddenly city after city, reacting to something that had presumably been abandoned a generation before, began building “vintage” ballparks, small and intimate, Disneyworld approximations of City Life. An afternoon of idle chit chat with strangers, of intimacy until the bottom of the seventh, when it was time to head to the parking lot, and beat the traffic on the long drive home. The fans may have lived elsewhere. But night after night, in cities across the country, they came to town for a few hours to abide in the world their parents, so eager to embrace a world other than that of their parents, had left behind.

And for a growing segment of those fans, home would soon be no further than a subway or cab ride away.

So it is that the Nets and Islanders come not to the Brooklyn of the Dodgers, or even the Brooklyn of my youth. This new Brooklyn, where my daughter lives (fourth generation!) and where my son goes to high school, is a destination. To live, and own, and shop, drink, eat well and wait on line for brunch at 2 p.m. on a Saturday because everyone in, say, Greenpoint – Greenpoint? – is just waking up.

The Nets and Islanders will play new games in a new arena that stands on the very spot where Walter O’Malley, had dreamed of building a great, domed stadium for his Dodgers, and who, thrwarted by the aforementioned Moses, took the team west.

If the past is any indication the various Brooklyns will take to the Nets, and Islanders, quickly, and will remain steadfast in their loyalty – and attendant conversation, in Twitter and Facebook and all the many inevitable team blogs – so long as the teams win. It has always been thus.

It pains me to think of what Brooklyn might have been had the Dodgers not left. But they did. And I left too. I come back from time to time, and thanks to the spectacular mismanagement of the Knicks by the ruthless dullard James Dolan, have decided to abandon the Knicks, my team since 1967, for the Nets. (Hockey I love as the one sport I don’t care about; everyone needs one, or else you may as well spend all your waking hours curled up with WFAN).

I will take the subway from Manhattan to the Barclays Center. I will wear my new Nets shirt, black with hanging sneakers emblazoned in white. I will chant “Let’s Go Brooklyn.”

And when the game is done I will go head to the exit, taking particular delight in the sound of all those many and different people talking about my new team.

Michael Shapiro, a professor at the Columbia Journalism School, is author of The Last Good: Brooklyn, The Dodgers and Their Final Pennant Race Together.