By Wayne Bokat

For a brief moment it seemed, just after the Knicks early 1970s mini-dynasty and before their 39-years of futility, there was a spectacular show that took place on Long Island.

For a brief moment it seemed, just after the Knicks early 1970s mini-dynasty and before their 39-years of futility, there was a spectacular show that took place on Long Island.

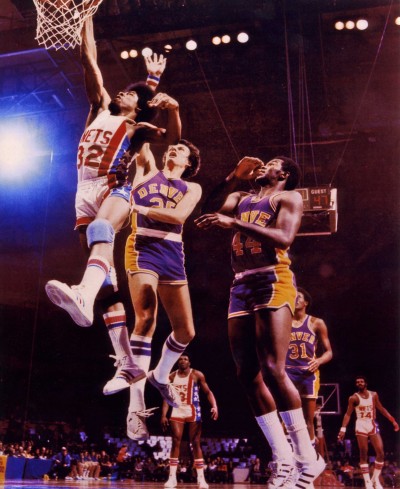

Led by Julius Erving, the New York Nets – who were playing at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale after having moved from, first Commack Arena and then a place called Island Garden in Hempstead – won two ABA championships in a three-season period from 1974 through 1976.

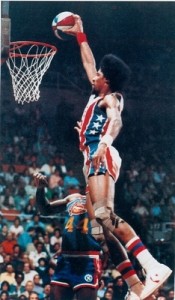

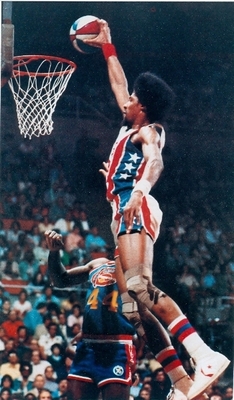

The Nets were good, but it was Erving, known as Dr. J, or simply The Doctor, who put on a show every time he played.

Yes, he did it in the NBA later on, as can be called up on YouTube where one can see his incredible move in the 1980 finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. He drives from the right side of the basket, is forced by a defender to go baseline, ends up underneath the rim, almost out of bounds it seems, and then somehow from the other side of the basket, spins the ball off the glass with his right hand.

Magic Johnson, then is his first year with the Lakers, said to his teammate, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar after witnessing what seemed even to him a miraculous move: “Should we give him the ball back and ask him to do it again?”

Though Dr. J made such moves in the NBA, he did it with more frequency in his five years in the ABA. Eventually, he lost some of his ridiculous “hops” (jumping ability) after several years in the NBA.

In his five years in the ABA, Erving averaged 28.7 points per game. In 11 NBA seasons, he scored 22.0 a game. But his field goal and free throw percentages were almost identical. He was the same player when he came into the NBA. He just couldn’t steal the show as often.

The ABA merged with the NBA after the 1975-76 season, and because there seems to be so little footage of the ABA, most of the magnificence of Julius Erving during those five years, is lost to the imagination.

In a sense, Dr. J remains forever young in his ABA form. He grew his hair – his afro – bigger, which was more common at the time. His hair was grander, so too was his game. His improvisational moves, his hang time and creativity, with all due respect to Michael Jordan, were more spectacular than Air Jordan.

For a lot of us who grew up on Long Island – I was born in 1962 – the Nets provided a measure of intimacy that the Knicks, or for that matter, the Yankees, Mets, Giants, Jets, Rangers, or even the Islanders, couldn’t.

I was a probably a year or two too young to have seen the Nets play at Commack Arena during a 1968-69 season in which they won an ABA worst 17 games. The dank ice-rink arena, converted for basketball games, usually only had several hundred fans in attendance. But there was a tradeoff for the losing. Fans got to get closer to the court and see the players for as tall and athletic as they really were.

The Nets transformation had begun during the summer of 1969, the summer of Woodstock – and the era of Knicks’ dominance – when Roy Boe bought the team. They acquired Rick Barry, a future Pro Basketball Hall of Famer, who convinced a generation of kids that they could make it to the pros shooting underhanded free-throws. And they hired a new coach, Lou Carnesecca, the former and future legendary coach of St. John’s.

Billy Paultz was brought in to play center. Nicknamed “The Big Whopper,” Paultz was 6-foot-11 and, though not agile, managed to figure out how to be an effective big man by developing an outside shot, a hook shot, and simply using his intelligence.

The Nets continued to get better adding players such as guard John Roche, a three-time All-American at the University of South Carolina, for the 1971-72 season. In the 1972 playoffs, the Nets reached the ABA finals.

They had beat Erving’s Virginia Squires in a spirited Eastern Divison finals. Erving was in his first season after starring at UMass, where he left after his junior year to turn pro.

But the Nets lost in the championship series to the Indiana Pacers. And after the season, Barry, the team’s star, was forced by the courts (the legal system courts) to move on to the NBA. Barry would play for the Golden State Warriors in the NBA the next season.

Although the Nets only went 30-54 (along with a red, white and blue basketball, a three-point shot, which the NBA didn’t employ until1979-80, the ABA played 84 games, two more than the NBA) the team did have the league’s Rookie of the Year in Princeton’s Brian Taylor in the winter of 1972.

Then the biggest move was made — a trade with the cash-strapped Squires for Dr. J. He was the ABA’s best player. They also added stars Larry Kenon and “Super John” Williamson and still had Roche, and other players who became popular with fans including Bill Melchionni, Wendell Ladner, who had his own fan club, and Willie “Rainbow” Sojourner.

I remember the first time I saw Dr. J play in person. I had heard of his brilliance, but seeing it live was stunning. Early in the game, he made one of his patented double-pump, hang and glide through the air, change hands, and put the ball in left handed on the other side of the hoop, moves.

When I think of that move, I remember something that Joe DiMaggio and later, Don Mattingly, said about why they played each game so hard. “There may be one person in the crowd today that’s never seen me play before,” was, essentially, the answer they both gave.

I like to think that The Doctor made that move early on that night because he knew I had never seen him play before.

The Nets started slowly that season, 1973-74, but finished strong and, in the year in which the Knicks futility (at least in terms of championships) began, they won their first ABA title. Two years later, they won a second ABA championship, in what would become the final year of ABA basketball, the 1975-76 season.

When the NBA and ABA merged for the following season, the Nets made a move that, at the time, hurt the way the Tom Seaver trade hurt Mets fans the next year.

Dr. J was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers, in large part because the Knicks were insisting on a large payout from the Nets for “invading their territory” in the NBA. The Nets simply couldn’t afford to pay Erving what they had promised him.

The Nets actually offered Dr. J to the Knicks as financial remuneration. Incredibly and maybe as a precursor to the team’s future mismanagement, the Knicks refused to take The Doctor. The repercussions for both franchises, the Nets and Knicks, seem to be felt, still, to this day.

Obviously the fan base wasn’t strong enough to keep the Nets on Long Island. The Nets moved to New Jersey, without Julius Erving, and the team, despite two consecutive trips to the NBA finals in 2002 and 2003, never could compete for the hearts and souls of New York’s fans.

Clearly, it is a different day.