This was a fun one to watch, right?

While the Brooklyn Nets went relatively standard for their last play in overtime — give the ball to Joe Johnson, get the hell out of the way — P.J. Carlesimo drew up something starkly different in the waning moments of regulation, turning Iso-Joe/HeroBall-Joe into Curl Screen Joe/Open Look Joe, and the playcall gave the Nets exactly what they needed.

The Nets ran a variation of a similar play they’d run against the Los Angeles Lakers to get Deron Williams a look earlier in the season, but with a few tweaks to make it a more successful option. Against the Lakers, the play was doomed from the start; against the Bucks, it got Brooklyn an open look.

Let’s break it down.

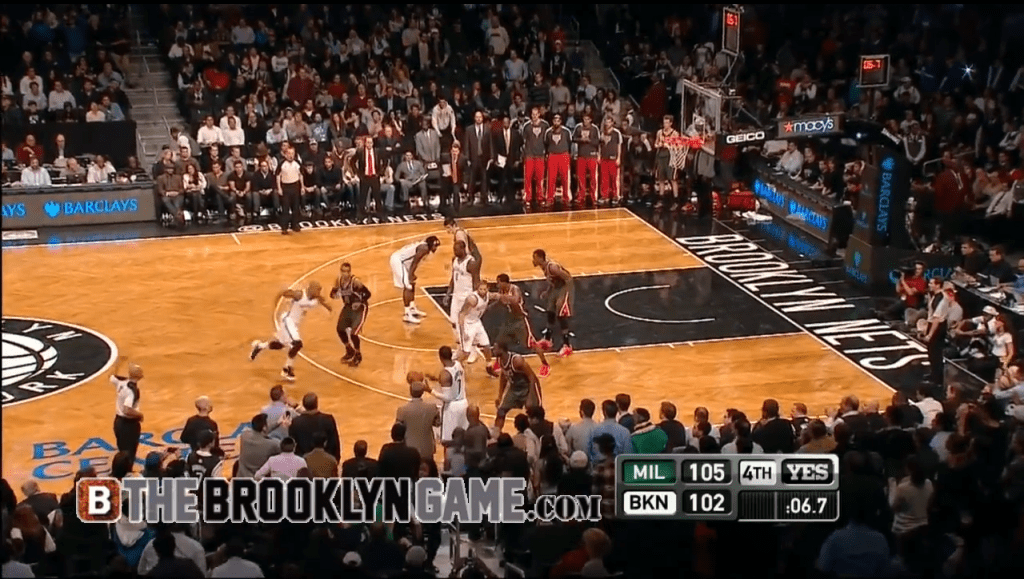

The play starts with Joe Johnson as the inbounds man, with Gerald Wallace and Andray Blatche on each elbow in the high post, with Deron Williams standing next to Blatche and Keith Bogans at the top of the key. Bogans already starts in motion before Johnson even gets the ball, and Williams pops out to receive the inbounds as Bogans curls around him.

One bit of Milwaukee’s strategy that’s clear here: even though the Bucks were up three, they chose to defend the paint, choosing not to give up a quick two and let the Brooklyn Nets beat them from beyond the arc. Look at Larry Sanders (guarding Blatche) and Ersan Ilyasova (guarding Gerald Wallace) in this shot and in the rest below: Sanders is playing a good four feet below Blatche, and Ilyasova isn’t much closer to Wallace. As you’ll see later, Johnson actually uses Sanders’ positioning to his advantage.

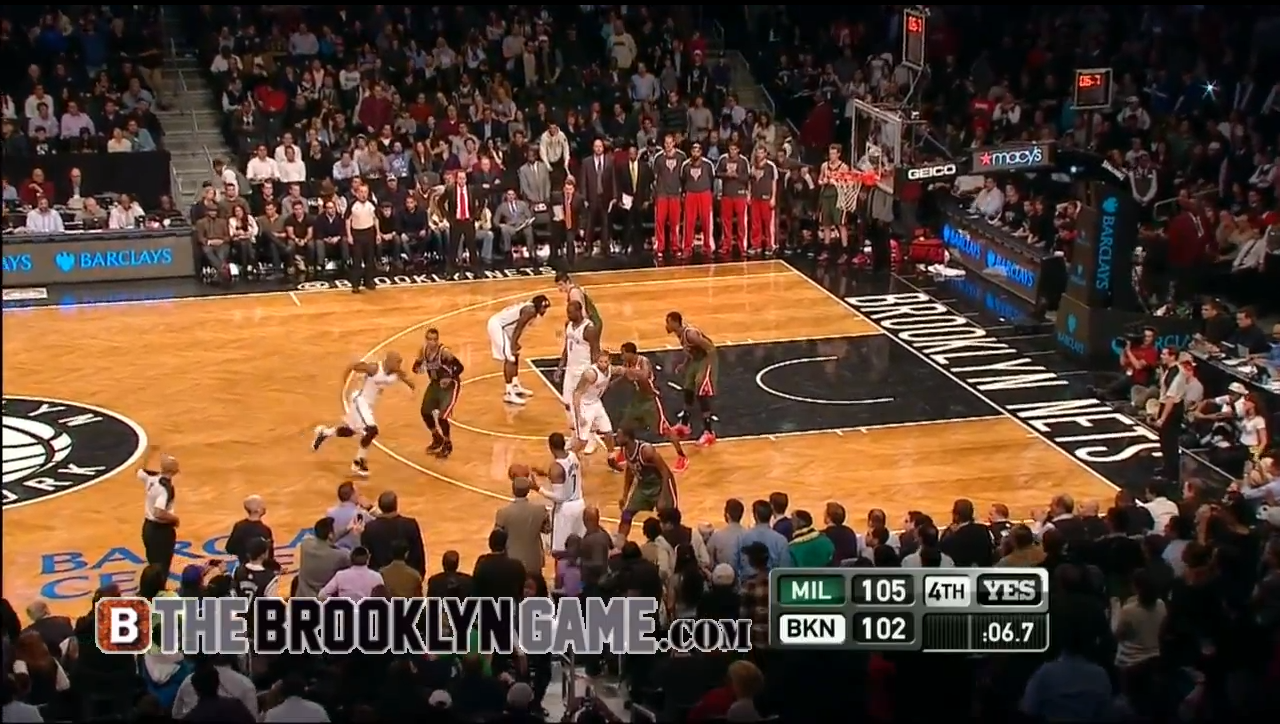

Johnson inbounds the ball and begins trailing Bogans in pinwheel fashion, while Blatche and Wallace prepare for whatever Johnson decides to do.

This is the part that’s ever so slightly a mystery to me. If you look closely, you can see Johnson with his right hand up as Bogans looks back. At first it appeared that Johnson was just trying to shake off contact from defender Luc Richard Mbah a Moute, but it also looks like a signal to Bogans to get out of the way. Even though Bogans stops to look back — which would perhaps indicate that there’s a potential screen to get Bogans an open shot in the right corner — Johnson seems to wave him off, seeing an opening up top.

(Thanks to the always-phenomenal coach & writer Brett Koremenos for talking out the scenarios with me on this one.)

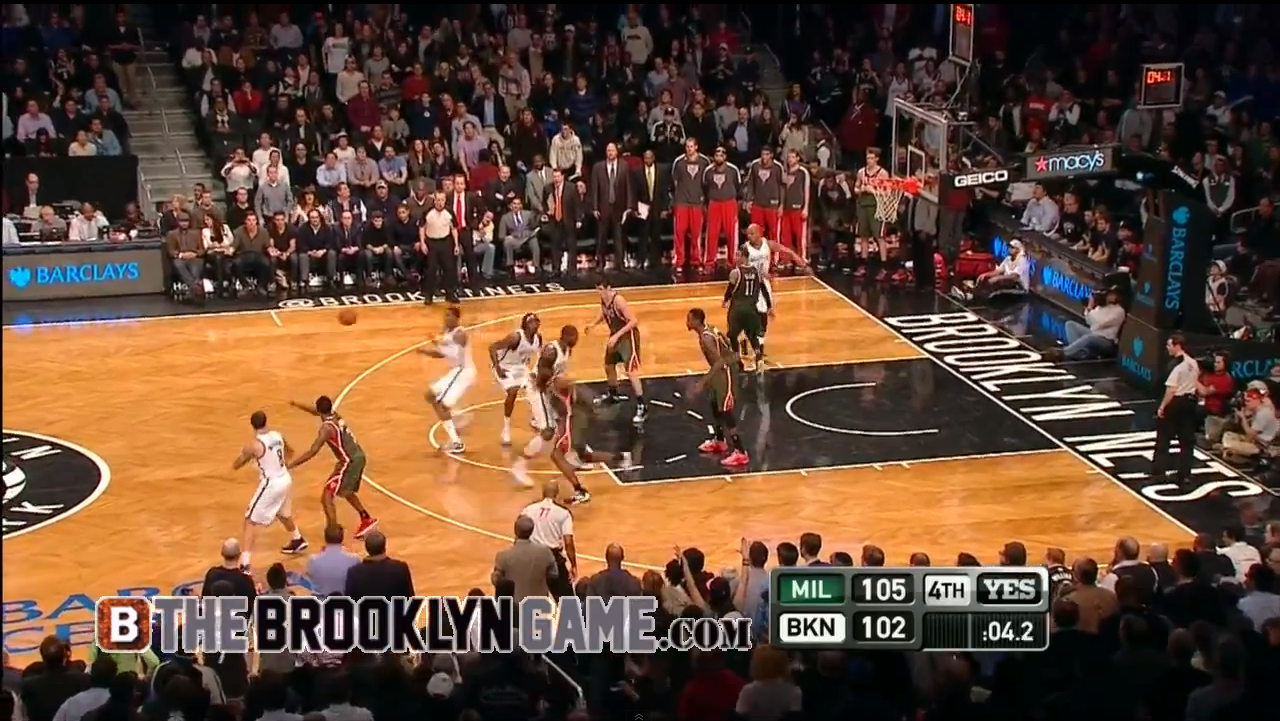

Here’s where Joe Johnson exploits Larry Sanders’s positioning. Look at this shot again: Johnson is running straight for the space just behind Sanders, and thus uses Sanders himself to screen Mbah a Moute, giving him his first bit of crucial space.

Above is the close-up on the replay: you can’t see Joe Johnson, because he’s on the opposite side curling up to the open middle, and Mbah a Moute, a normally excellent defender, is one step out of the play.

With Mbah a Moute previously occupied with his own man screening him, this gives Blatche a chance to set himself properly up to add time & space between Johnson & Mbah a Moute with a solid screen. As for Johnson, the pass is already in the air, and the shot is already locked in.

With six seconds left and down one long-range shot, that’s about as good a look as you can get.

—-

More notes:

The principles between this successful look and the play that failed against Los Angeles are largely the same — run your guard around and through a screen to get him an open look — but two major tweaks gave it vast improvement:

- Joe Johnson utilized two screens to get open: one by Andray Blatche, and one creatively by Larry Sanders. In November, Deron Williams ran in a circle. Carlesimo’s playcall called for the inbounder Johnson to make the choice in the curl screen: with both Wallace and Blatche ready to set screens, Johnson saw an opening in the middle of the floor and darted through it. The call in November saw Williams darting straight into Kobe Bryant’s waiting defense; part of that is that Los Angeles defended the play smartly, but if there’s not an opening in the middle, there should be a secondary option for your best player to get the ball.

- Carlesimo’s playcall used the “decoy shooter” Keith Bogans more actively in the play; it was a possibility that the ball would end up in Bogans’ hands, and the defense had to pay attention to his movement if even for a split second. The call in November had Watson floating to the corner without any attention to the play’s movement.