The Brooklyn Nets face a daunting task: in the history of the NBA playoffs, an eighth seed has knocked off a one seed only five times.

Even with extra-long odds, not all eighth seeds are made equally, and the Nets are one of the weaker NBA playoff teams in recent history. So to do something that’s been done only a handful of times in NBA history, it’ll take great basketball to knock off the East’s premier team.

What we’ve seen through the first two games is an amalgamation of all of the mixed-up execution the Nets have faced for the majority of this year. The Nets have turned the ball over 33 times in the opening two games: that’s 33 less chances at scoring, or 33 fewer breaths of air for a team on life support.

It’s common to see a player’s body language droop immediately after needlessly giving the ball to the other team. But more than that, live-ball turnovers can spoon-feed the opposition’s offense. For a team like the Atlanta Hawks, who are already full of offensive firepower, additional scoring opportunities are like adding heat to a grease fire.

Take for example this Deron Williams gaffe from game two:

The Hawks are a stingy defensive team and have enough size and athleticism at all positions to bother an offense. But this Williams turnover had nothing to do with that. Here we’re looking at either a lack of concentration or just pure laziness. Either way, it’s preventable.

This not only prevented the Nets from a shot at the rim, but it triggered a Jeff Teague alley-oop to Paul Millsap, as well as an immeasurable wave of momentum.

These lack-of-concentration turnovers happened often over the first two games. Remember, the Nets only lost Game 2 by five points. With a margin that small, the Nets did not need to reduce their sixteen turnovers to zero, but perhaps saving three or four of them would have gotten the Nets to Brooklyn with a split series.

The next time a basketball team plays a flawless game will be the first. Turnovers are going to happen against a good team. The key is to manage and limit those mistakes. Unforced turnovers crippled the Nets at times, but the Hawks snuffed out some of the Nets’ core offense.

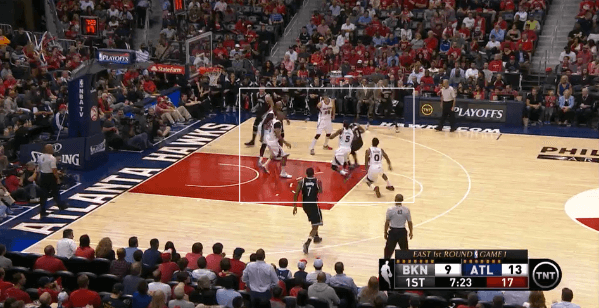

Taking an action that is designed to give the offense an advantage, such as a ball screen and converting into a defensive advantage, is next-level stuff. Watch how the Hawks defend this side ball-screen:

In the above, Alan Anderson gets a catch deep in the corner, a tough place to do anything other than catch and shoot. With the sideline and baseline acting as second and third defenders, your options are limited.

To make matters worse, Mason Plumlee scurries over to set a ball screen, which brings an additional defender and congestion to an already tight situation.

The Hawks have been ICEing, or downing, these side ball-screens, meaning they’re taking away the middle and forcing the ball handler towards the baseline. But with zero real estate to work with, both Jarrett Jack and Alan Anderson have few options.

Plumlee acts as the pressure release, which also thrusts him into the role of decision maker. But unless Plumlee’s decision is “how hard should I dunk this ball?”, things are not likely to work in the Nets’ favor.

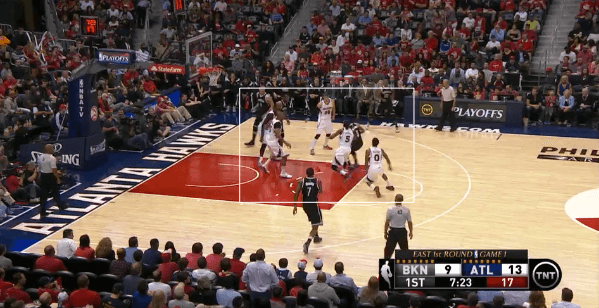

Here’s another example, with similar results:

After some token Nets motion, Jarrett Jack winds up with the ball in the corner, and not in a catch-and-shoot situation. Matters get complicated when Plumlee goes to screen and the Hawks ICE the coverage, essentially applying a four-cornered trap on Jack.

With almost no passing angle, Jack is forced to loft a long pass over the top of the trap, which is intercepted and converted into another Hawks bucket.[note]For fun, watch Earl Clark track back on defense, and notice his half-second hesitation and realization just how close he was to preventing the Schröder layup.[/note]

These issues could be somewhat alleviated with better spacing. But spacing is an issue in the Nets offense, too. Take a look at the Nets spacing after this Deron Williams/Joe Johnson pick-and-roll sprung Williams into the middle of the court:

Brook Lopez and Thaddeus Young are within feet of each other, and neither is in good position to receive a pass. Even worse, both of their defenders block Williams’s path to the basket. Markel Brown out on the wing is not a threat to the Hawks, and his defender Kyle Korver sits deep in help position. This poorly spaced possession lets all five Hawks defenders guard Williams, and do so while covering only about 10 square feet of court. Cycle through the rest of the Nets turnovers and you’ll notice a lot of these issues popping up: poor concentration, poor spacing, poor play.

The good news: these issues are fixable, and despite all of the giveaways, the Nets had a chance to win both games. The bad news: the reality is that this team is flawed, and probably in ways that they can’t overcome against the Hawks.

Only two losses separate the Nets from elimination, and they’ll need to be near-perfect from here on out. But from the look of things, they’re a long way from perfect.